Blog

Blog

Últimos mensajes

Últimos mensajes

Temas mas recientes

Temas mas recientes

|

Thank You Posts

Show post that are related to the Thank-O-Matic. It will show the messages where you become a Thank You from an other users.

Mensajes - senslev

Mensajes - senslev

https://elpais.com/economia/negocios/2024-06-01/asi-se-ha-convertido-el-alquiler-de-habitaciones-en-el-salvaje-oeste-inmobiliario.htmlAsí se ha convertido el alquiler de habitaciones en el ‘salvaje oeste’ inmobiliario

El precio de una estancia con derecho a zonas comunes ha subido un 42% en cinco años. Los propietarios buscan mayor rentabilidad y escapar de los controles, aunque los jueces empiezan a proteger a los inquilinos

JORGE ZAPATA (EFE)

Sandra López Letón

SANDRA LÓPEZ LETÓN

Madrid - 01 JUN 2024 - 05:45 CEST

En las ciudades de Barcelona, Bilbao, Madrid, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Palma de Mallorca y Pamplona el precio por alquilar una habitación no baja, en ningún caso, de los 500 euros al mes. Pagar por un dormitorio, un baño, un salón y una cocina (estas tres últimas estancias compartidas con más personas) cuesta 466 euros mensuales de media. Es un 42% más que hace cinco años y un 76% superior a las cifras de 2015, según el portal Fotocasa.

El alquiler de habitaciones en España ha sufrido una metamorfosis importante en los últimos años hasta convertirse en protagonista (involuntario) en la vida de miles de personas en nuestro país. En muy poco tiempo ha pasado de ser un mercado pequeño, asequible y solo vinculado a jóvenes, sobre todo estudiantes, a ser la única opción para muchos inquilinos —aunque muy costosa y cada vez más— y un negocio interesante para los propietarios que hasta ahora solo habían destinado sus pisos al alquiler de larga estancia. La diferencia es que se suelen regir por el Código Civil y no por la Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos (LAU), que fija la duración del contrato en cinco años, entre otras cuestiones. El Ministerio de Vivienda ya ha puesto la lupa sobre esta modalidad de alquiler por considerar que está contribuyendo a elevar los precios en las ciudades. La ministra Isabel Rodríguez desveló en una entrevista en EL PAÍS, el 14 de abril, su intención de regularlo al estar “dejando a las personas desprotegidas”.

Cada vez hay más ciudadanos que alquilan habitaciones y no por gusto, sino por la imposibilidad de pagar un alquiler íntegro. Nada menos que el 44% de los españoles que comparte piso lo hace porque no puede afrontar un alquiler entero, de acuerdo con Fotocasa.

No hay un registro oficial de alquiler por habitaciones y, además, es bastante complicado seguirle el rastro dado que hay pagos en negro. El Observatorio del Alquiler, elaborado por la Fundación Alquiler Seguro y la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, aporta algunos datos: “El crecimiento de habitaciones en el último año a nivel de oferta estaría en torno a un 26,2%. Y el aumento del precio de habitaciones habría subido un 8,3%”.

El portal Fotocasa ha analizado la evolución de la oferta en los últimos años en algunas de las ciudades donde los precios son más altos. En Madrid el saldo fue negativo hasta 2021, año en el que la oferta creció un 218%. En 2024, hasta abril, ha aumentado un 24% con respecto al mismo mes del año anterior. En Barcelona, ha crecido un 24% interanual y en Málaga un sorprendente 96%.

Los propietarios han encontrado un sector más generoso. La rentabilidad del alquiler tradicional de larga duración es del 6,6% bruto anual y del 9,5% en el caso de las habitaciones, de acuerdo con el análisis de Fotocasa. “Es casi un 50% superior a alquilar una vivienda entera. El precio de una habitación ronda los 466 euros, mientras que un casa completa de unos 80 metros cuadrados se encuentra alrededor de los 900 euros. Si el inmueble cuenta con tres habitaciones, la rentabilidad bruta supera la del alquiler convencional”, explica María Matos, directora de estudios y portavoz del portal.

Fiscalidad

El propietario considera que es un mercado más flexible y, además, escapa —o eso cree, porque no siempre será así— al control de la LAU y a los límites a la actualización de la renta fijada por el Gobierno (un 3% en 2024). Casi pleno. “El propietario siente que es una alternativa a la hiperregulación, que no es un condimento que favorezca al mercado y, además, es algo más rentable”, afirma Ana González, vicesecretaria de la Confederación de Asociaciones de Propietarios. Aunque, recuerda González, “esta modalidad no tiene desgravaciones fiscales, como sí sucede con el alquiler tradicional. Tributas al 100% y eso hace perder algo de rentabilidad”.

Y así, en busca de mayor rendimiento y certidumbre, es como abandonan el arrendamiento tradicional para dar el salto al alquiler de habitaciones en el que, además, se pueden acoger a múltiples opciones: alquiler por años, por meses o por días. “La motivación de alquilar habitaciones por periodos cortos, normalmente por días, es diversa: esquivar ley de vivienda, esquivar regulaciones turísticas locales, disponer de más margen de actuación para poder saltar de un mercado a otro (residencial, turístico, temporada, habitaciones), esquivar control fiscal…”, comenta Sergio Cardona, analista del Observatorio del Alquiler.

El auge del alquiler de habitaciones ilustra a la perfección los profundos cambios sociales que se están sucediendo y que tienen como causa principal la crisis de la vivienda. “El alquiler de habitaciones se ha convertido en los últimos años en una solución habitacional que ha saltado la tradicional cohorte de edad de los jóvenes para pasar a ser una solución en casi cualquier edad”, dice Cardona.

Eduardo Fernández-Fígares, del despacho Abogados para Todos, ratifica la llegada de más perfiles: “Antes eran los estudiantes y poco más y ahora encontramos trabajadores de todo tipo, empujados por los altos precios de las viviendas completas y por la falta de oferta”. Un ejemplo muy clarificador es Cádiz, una provincia muy golpeada por la crisis y el desempleo, donde la media de edad del alquiler por habitaciones es de 58 años. “Esto mismo, con grupos de edad que superan los 40 años, está pasando en muchas provincias, donde el alquiler por habitaciones está siendo, por precio, la opción habitacional para personas con bajos ingresos, al no poder acceder al alquiler de una vivienda”, explica Cardona.

El arrendamiento de habitaciones se regula por el Código Civil y no por la LAU, lo que genera seguridad en el propietario porque, en teoría, no está obligado a alquilar por periodos de cinco años y, en teoría también, puede ser más sencillo desahuciar a los inquilinos que no pagan. Pero no siempre es así. El abogado Fernández-Fígares, especializado en desahucios por impago de alquiler, habla de “una falsa ilusión que está haciendo que se saquen al mercado contratos de habitación en lugar de vivienda completa”.

Explica que “aunque el propietario crea que es un contrato sometido al Código Civil puede encontrarse con la sorpresa de que el juez diga que está sometido a la LAU. Esto va a depender de si esa habitación constituye la vivienda habitual del inquilino”.

Le sucedió el pasado febrero en una demanda de desahucio por impago de alquiler de una habitación. El juez dictó en el auto que una habitación puede ser vivienda habitual, es decir, el inquilino puede tener derecho a la protección que se ofrece cuando se trata de una vivienda habitual completa. “Y que el hecho de pasar por alto ese dato tan importante haría que el inquilino estuviese desprotegido por no poderle ser de aplicación la normativa de vulnerabilidad de la ley de vivienda (en concreto el nuevo artículo 441.5 LEC) que obliga al juzgado, de oficio, a informar a los servicios sociales de que se ha puesto una demanda frente a un inquilino, para que estos se pronuncien acerca de si el inquilino es vulnerable o no”.

Ya, ya, sin problemas. En el post anterior sobre este tema puse links que tratan las diferentes sensibilidades. De hecho en este mismo mensaje que comentas, el autor que critica el tecno optimismo en relación con el tema baterías y transición energética con renovables, no tiene claro que el origen del cambio climático (que se reconoce en general) sea por el CO2. Otros hablan de ciclos solares, sobre el vapor de agua, y que el aumento de temperatura se está exacerbando por la erupción del volcán de Tonga y por el fenómeno de El Niño, que por cierto, termina ya y empieza el de La Niña y otros fenómenos como la reducción del SO2 en los carburantes usados por los barcos (esto en el aumento de la temperatura del agua del océano/mar)

Sobre los datos y la honradez de quien los interpreta, ¿nos fiamos o no nos fiamos?. Cuando me hago esta pregunta, pienso lo que tiene que ganar o perder la persona que se expone o involucra al tratar el tema. No creo que Turiel, Nate Hagens, Tom Murphy, el autor de Beamspot o Javier Vinós ganen nada exponiéndose como lo hacen (cada uno con sus opiniones e investigaciones). Lo que sí tienen claro es que hay cambio climático, pero no se ponen de acuerdo en el origen y en la gravedad.

Los que sí ganan son los de la transición energética fake y los que nos meten en guerras que nos empobrecen.

Personalmente creo hay cambio climático y el ser humano es, como poco, en parte responsable. Sobre el tema del peak-oil y combustibles fósiles, creo que empezamos el declive. No son lo mismo 2000 millones de almas que 8000 millones y el impacto que tiene en la naturaleza el nivel de depredación que requiere nuestro estilo de vida. Tampoco es lo mismo el EROI de antes que el de ahora.

El tiempo dirá. No creo que nadie lo sepa, cero certezas, pero hay pistas.

y la gente me acusa de gruñón, de"adaptate" , y de " es lonqie hay". "Es lo que hay". Frase comodín para todo. Me pregunto si siempre se hubiese pensado así, ¿se habría evolucionado en algo?. Nada cambiaría. Gente asesinada, "es lo que hay"; inaccesibilidad a la vivienda, "es lo que hay"; 50 grados de temperatura "es lo que hay"; tarados con motosierra, "es lo que hay"; inflación, "es lo que hay"; guerras absurdas que van en contra de la población, "es lo que hay"; natalidad nula, "es lo que hay"; plutocracia, "es lo que hay"; cleptocracia, "es lo que hay"; hijoputismo, "es lo que hay". "Adaptación y flexibilidad", o lo que es lo mismo, cambia de valores según sople el viento y si eso significa reventarle la vida al de al lado, "es lo que hay". Es lo que hay. La vida es asín.

Cero certidumbre en bolsa, si fuese así, no podría ser.

A no ser que te refieras a que está todo amañado, entonces, para los que lo controlan sí que hay certidumbre, para el resto es todo una ilusión y de ahí la transferencia de riqueza de la mayoría a esos que lo controlan todo (en teoría certidumbre a lo largo del tiempo, no a corto plazo, por lo que volvemos a lo de que no hay certidumbre).

O igual no se a qué te refieres, que también puede ser.

Por definición certidumbre y bolsa son dos términos incompatibles. En la vida también. Claro, senslev... pero es que el problema es otro.

Quieren certidumbre. ¿Para qué? Para posicionarse en Bolsa. Tú futuro, tu bienestar les importa un carajo. Quieren imponer algo, y les da igual qué... Sólo quieren apostar a caballo ganador.

Entonces: Bolsa, ni tocar. Medidas consensuadas y razonables. Ciencia, toda la que se pueda. Paciencia. (Y barajar, je, je.)

Ya he puesto diversas fuentes que tratan sobre el cambio climático. Las vuelvo a poner. Los datos, la interpretación de los datos y la honradez de quien los interpreta, asumiendo el conocimiento correspondiente, ya no es mi problema. Esto es como la inflación, según ppcc no hay inflación o es inflación falsa, bueno, pues mi percepción es otra. ¿Hace más calor que antes y el clima ha cambiado?, sí, esa es mi percepción, ¿comparándolo con qué?, pues con el tiempo que llevo vivo básicamente. https://www.rankia.com/blog/game-overEjemplo de la AMOC: https://www.rankia.com/blog/game-over/6253442-manipulacion-mediante-mala-ciencia-ficcion-climaticahttps://www.youtube.com/@thegreatsimplification/featuredhttps://dothemath.ucsd.edu/https://escholarship.org/uc/energy_ambitions

https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/2024/05/07/277-at-the-limits-of-monetary-possibility/#277: At the limits of monetary possibility

Posted on May 7, 2024

HOW DOES THIS END?

On two occasions in modern times, central banks have found themselves obligated to pour huge amounts of newly-created money into the system. The first instance was the global financial crisis of 2008-09, and the second was the coronavirus pandemic of 2020-21.

Neither of these events was anticipated, though the first one certainly should have been. You would have to be very brave indeed to bet against another out-of-the-blue shock forcing central bankers back into flooding the economy with liquidity.

In fact, the very structure of the financial system makes a future shock inescapable. Over the past twenty years, and depending on the definitions used, each dollar of growth in the global economy has been accompanied by between $3 and $8 of newly-created financial liabilities.

Simply stated, the financial system has been allowed to grow far more rapidly than the underlying economy itself, and this creates a wholly unsustainable set of trends which will lead to a drastic reset of the relationship between the economy and the financial system.

This has happened because we’ve been trying to counter, whilst at the same time denying, structural deterioration in the global economy. Driven by the depletion of oil, natural gas and coal resources, the material costs of energy have been rising relentlessly, and, contrary to widespread assurances, renewables cannot provide a new source of abundant low-cost energy to the economy.

In essence, we’ve been trying to overcome material economic deceleration with monetary stimulus, a technique that cannot work, but for which no alternative exists.

As you may know, we have a limitless capability for the creation of money, but the banking system can’t lend energy or other natural resources into existence, and central banks cannot conjure them out of the ether.

Building the next crisis

The main driver of super-rapid monetary expansion hasn’t been central bank money-creation. Rather, the central banks have acted as the last line of defence when credit excess, generated elsewhere, has threatened to fracture the system.

Not later than 2007, the global credit mountain had reached a scale at which it could no longer be serviced at normal rates of interest. The purpose of subsequent rate-slashing, reinforced by QE, was to prevent the servicing of this credit mountain from becoming completely unaffordable.

But making credit cheap to service also means making it cheap to obtain. We need, but have yet to find, new tools for managing the supply of credit to the economy in ways that do not exacerbate systemic risk.

As the world’s stock of credit has grown, the system has simultaneously become both more complex and more dangerously inter-connected.

In the modern economy, in which most money is loaned into existence, each unit of money is tied to a corresponding obligation. Accordingly, whenever we try to use credit expansion to stimulate the flow of activity in the economy, we simultaneously add to the stock of financial commitments.

Meanwhile, tightening the regulation of conventional banks has pushed ever more of the process of credit expansion into the unregulated, and higher-risk, “shadow banking” (NBFI) system, where even quantitative data is neither complete nor timely.

The next financial crisis is likely to originate in some esoteric part of the system that most members of the public have never even heard of. When this happens, the current policy of countering inflation by raising rates, and reversing QE into QT, will, by force of necessity, have to be thrown into reverse.

We’ve always known that the unanchored fiat money system creates a temptation for the authorities to resort to excess money-creation, thereby undermining the purchasing power of money.

Less thought seems to have been devoted to the possibility, which has now become a probability, of them being compelled to expand the stock of money by failure somewhere within the top-heavy, super-complex, dangerously interconnected and excessively-stressed financial system itself.

Hitting the panic-button

Both the 2008-09 and the 2020-21 interventions were inflationary, as the creation of new central bank money always is. The difference, though, was the point at which this inflation showed up.

During and after the GFC, the inflationary effects of QE were largely confined to capital markets, creating the “everything bubble” in asset prices. During the pandemic, however, newly-created money was channelled, via enormous government deficits, into the broader economy of households and businesses.

By convention, soaring asset prices aren’t included in headline definitions of inflation, and it was only when QE largesse was redirected to households that measured consumer price inflation took off. This taught everyone something that many had understood all along, which is that, notwithstanding routine assurances to the contrary, central bank money creation is inherently inflationary.

Our attitudes to these differing forms of inflation are inconsistent. When asset prices soar, the (generally older) owners of assets rejoice at the increase in their paper wealth, whilst scant attention is paid to the plight of younger people, whose aspirations to acquire homes and other assets get priced ever further out of their reach.

When consumer price inflation takes off, on the other hand, households experience hardship, voters get angry, and officialdom sits up and takes notice.

This is why, since 2021, most central banks – with the noteworthy exception of the Bank of Japan – have adopted counter-inflationary, restrictive monetary policies, implemented by raising policy interest rates, and by reversing QE into QT.

This plan hasn’t yet faced a serious challenge. The collapse of SVB was a minor event, whilst the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget was just a little local idiocy – but both set the hands of central bankers quivering over the QE-button.

In one sense, though, the Truss-Kwarteng fiasco was instructive – the Bank of England wasn’t forced to intervene by a falling currency alone, or by surging gilts yields, but by the implications for another part of the system, which, in this instance, was pension funds made vulnerable by the use of LDI (liabilities-driven investment), with its dependency on gilts prices as collateral. We could call this a ‘second-hand’, ‘second-order’ or unintended consequences type of risk.

This is a prime example of complexity risk in the sprawling, interconnected system of global credit.

The theory of restrictive monetary policy is that inflation can be brought back under control by cooling the rate of borrowing. One of the attendant risks is that raising the cost of capital could trigger a market crash by puncturing the “everything bubble”, which was created through the provision of vast amounts of recklessly cheap capital. Another is that these policies might simply fail to bring headline inflation under control.

What we are waiting for – whether we acknowledge this or not – is the next really big test of central bankers’ resolve. We don’t, and probably can’t, know exactly where this will come from – but we do know that it will.

Found in translation

Through these various gyrations, monetary policy has become the only game in town. Where investors, analysts and commentators once concentrated on a host of issues as diverse as OPEC oil price intentions, political or geopolitical stresses, trade balances or the direction of economic activity, the debate has shifted to the new centre-ground of interest rate forecasting.

This, as Ann Pettifor has said, “is tricky terrain for economists, because – remarkably enough – they are not routinely trained in the theory of money and banking. You can get through an economics degree, even an economics career, without pausing to think seriously about either”.

“To understand how grave an intellectual vacuum this leaves”, she continued, “imagine the chaos if physicists working on space projects had not been trained in the theory of gravity – a concept that is fundamental to physics in the way that money is fundamental to the economy”.

This isn’t territory onto which any non-specialist should lightly venture. But Surplus Energy Economics uses a concept which we can claim to be unique, and which can add value to the debate.

This is the concept of two economies. Instead of referencing “the” economy, and interpreting it entirely in monetary terms, we recognise that the “financial economy” of money, transactions and credit exists in parallel with the “real economy” of material products and services.

This understanding enables us to recognize that inflation, and numerous other economic processes, are functions of changes in the relationship between the monetary and the material economies.

From this perspective, we can define prices as “the monetary values ascribed to material products and services”. We can go on to state that “money has no intrinsic worth, but commands value only as an exercisable claim on the output of the “real” or material economy”.

Effective interpretation, then, requires the conjoined analysis of the monetary and the material.

Each of these two economies has its own identifiable processes. The real economy operates by using energy to convert raw materials into products. (This definition also embraces services, because no service can be provided without physical artefacts, and there is no such thing as an ‘immaterial economy’).

The critical processes in the financial economy are the creation, deployment and elimination of money as credit, and the interplay between the flow and stock of money in the system.

We need to be aware that the monetary and the material economies have an in-built tendency towards equilibrium, because the value of money exists only as a claim on the material. If, put at its very simplest, we double the flow of money in the system, but are unable to increase the size of the material economy, then the rate of exchange between the two must halve, to bring them back into balance.

In short, if we create excess claims in the system, these excesses must be eliminated in a process that can be thought of as value destruction. This occurs either through formal default or through the informal or soft default of monetary devaluation through inflation.

The dynamics of self-delusion

What, then, has actually been happening to the “two economies” in the comparatively recent past?

The answer, simply stated, is in three parts.

First, material prosperity has carried on growing, though the rate of increase has slowed to a microscopically small amount.

Second, the flow of monetary activity measured as GDP has grown at a higher and seemingly-satisfactory rate.

Third, though, the stock of financial commitments – the aggregate of debts and quasi-debts – has soared, drastically out-pacing the economy itself.

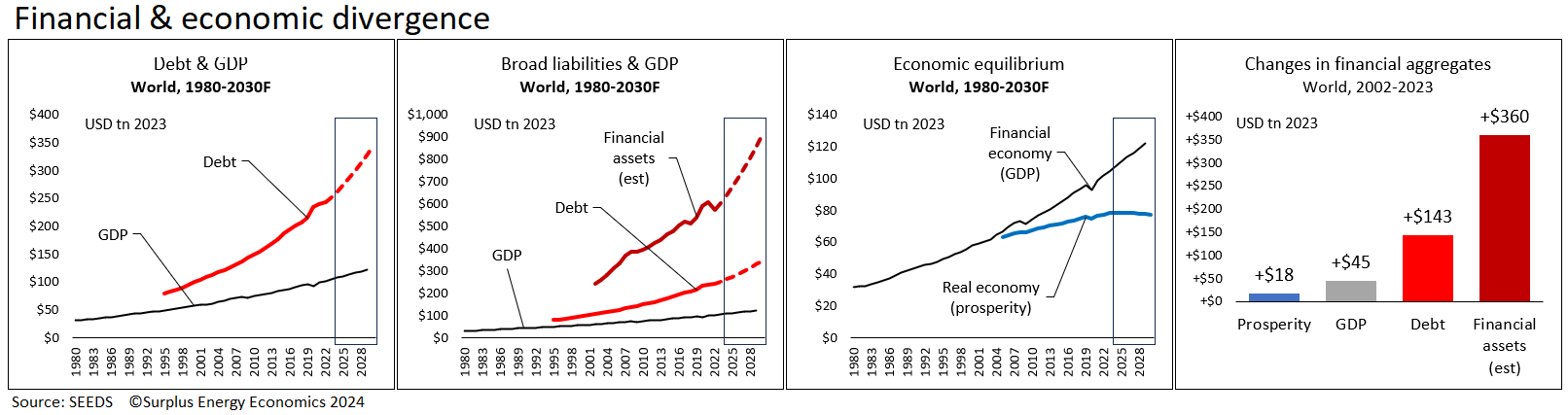

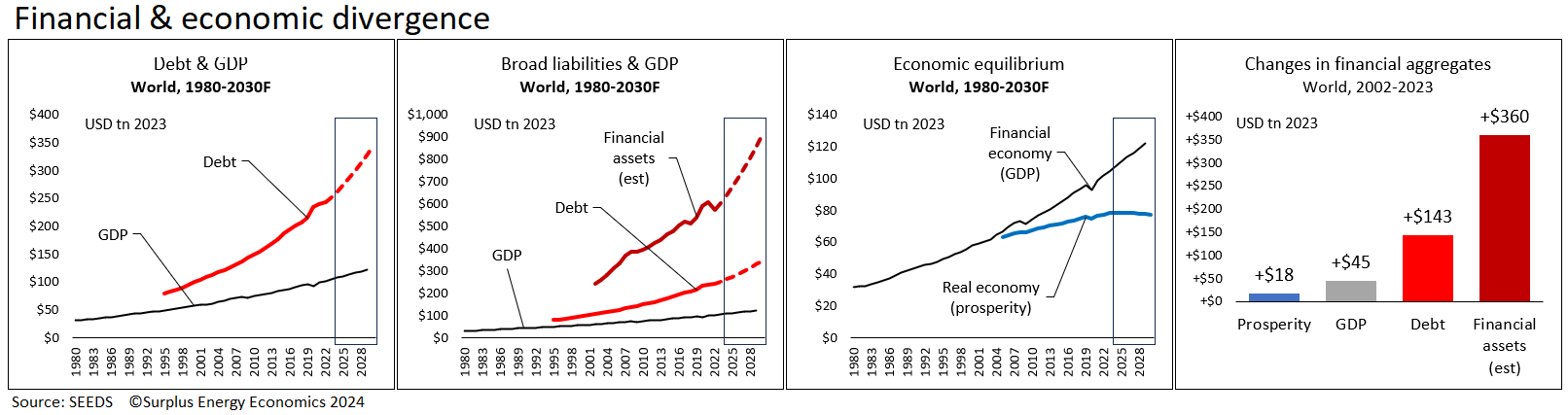

We can quantify these trends, with all data used here stated at constant 2023 values, in dollars converted from other currencies at market exchange rates.

Since 2002, global debt has increased by $143tn, or 130%. But broader financial assets – which are the liabilities of the government, household and private non-financial corporate (PNFC) sectors of the economy – have grown by about 150%, or $360tn, over that same period.

This latter number can only be an estimate, because some jurisdictions choose not to report financial assets data to the Financial Stability Board. The FSB is a monitoring organisation, not a regulatory one. The estimates cited here are likely to be understatements because, whilst most sizeable economies are included in the FSB data series which start in 2002, only two of the world’s specialised, hugely-leveraged financial centres – Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands – supply data to the FSB.

Over that same period, global real GDP expanded by $45tn, or 74%. This means that each dollar of reported growth between 2002 and 2023 was accompanied by $3.20 of net new debt, or by about $8 of net new broad financial assets.

The resulting trajectories are unsustainable, as the accompanying charts illustrate – debt is fast out-pacing GDP, broader liabilities are in turn out-growing both debt and GDP, whilst material prosperity is far adrift even of financial flow, let alone of monetary stock,

Moreover, the stock and flow data series aren’t really discrete, since credit expansion results in an increase in the aggregate of financial transactions which are measured as GDP.

Put another way, we are lending money into existence, and then counting the spending of that newly-created credit as “activity” for the purposes of measuring the size of the economy, whilst ignoring questions about the servicing or repayment of debt.

On this basis, we’re entitled to conclude that we’ve been manufacturing “growth” through the breakneck expansion of credit, and that this “growth” could only be regarded as genuine if we assumed that debt and broader liabilities need never to be honoured.

If it takes somewhere between $3 and $8 of new debt or quasi-debt to generate a dollar of GDP growth, paying off debt incurred in the present from growth generated in the future is a mathematical impossibility.

An example here is the United States which, during 2023, generated reported real growth of $675bn on the back of a $2.4tn fiscal deficit.

America, of course, is in a privileged position, able to borrow readily from other countries because of the reserve status of the dollar, and the use of USD in energy and other critically-important commodity markets.

Even the US, though, can hardly carry on adding government debt at a rate of $1 trillion every hundred days before the markets, and the public, start to ask hard questions about the real character of economic “growth”, and recognise that – whether in America or elsewhere – our growing mountains of debt and quasi-debt can never be honoured ‘for value’ from the proceeds of “growth”.

To tie these various numbers to underlying reality, SEEDS calculates that global material economic prosperity increased by less than 8% between 2002 and 2023, a period in which aggregate liabilities expanded by close to 170%, and non-government liabilities by an estimated 180%.

These numbers look a bit better in PPP- rather than market-converted terms, because the purchasing-power parity FX convention attaches proportionately greater weight to economies such as China, India and Russia.

But the fact remains that credit expansion is driving reported growth at rates which, whilst they far exceed underlying material reality, can never catch up with the rates at which debt and quasi-debt are growing. SEEDS undertakes these calculations by backing out the inflationary credit-effect element in GDP growth, and deducting the all-important Energy Cost of Energy, or ECoE, from the resulting calculation of underlying or ‘clean’ economic output.

We could, at some later date, explore the process of credit creation within the regulated banking and the unregulated “shadow banking” (NBFI) sectors. But it suffices, for now, to know that we have long been fabricating economic “growth” by allowing the stock of credit, and therefore of money, to drastically out-grow any meaningful measure of the flow of value within the economy.

Together, the scale and complexity of the bloated credit system mean that – probably at some esoterically-technical level – something is going to break, forcing the central banks into trying to prop up the system by flooding the economy with money.

But we can’t “print” our way to monetary stability, any more than we can borrow our way to prosperity.

This, unfortunately, is going to have to be learned the hard way.

Para mi lo estúpido es no dar la posibilidad que sea una mezcla entre lo humano y lo natural. Es decir, ¿8000 millones de personas arramplando con todos los recursos naturales, contaminación de todo tipo vertida al medio y miles de millones de máquinas, no han contribuido en nada a que el clima cambie?. Pregunto.

Así es, y tan estúpidos como los que lo achacan al factor antropogénico

|