Blog

Blog

Últimos mensajes

Últimos mensajes

Temas mas recientes

Temas mas recientes

|

Esta sección te permite ver todos los posts escritos por este usuario. Ten en cuenta que sólo puedes ver los posts escritos en zonas a las que tienes acceso en este momento.

Mensajes - Derby

1

« en: Ayer a las 09:05:24 »

https://www.ft.com/content/32009538-4d40-4281-858f-75587149ba0aSwitzerland stirs Brexit ghosts in push for EU access

Referendum looms on single market deal that includes concessions on money, migration and judicial power

After more than a decade of talks with Brussels, Switzerland has reached a deal to keep and improve its access to the EU’s single market. © Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

A proudly independent European nation confronted with a stark political choice: keep EU single market access but only by making financial payments, taking migrants and giving up judicial power.

This time the question is not one for Brexit Britain — but Switzerland.

After more than a decade of grinding talks with Brussels, the Alpine country has reached a deal to keep and improve its access to the EU’s single market.

But the agreement — which will be put to a referendum — includes all the same thorny issues that have bedevilled the UK-EU relationship, including budget contributions, migration policy and the role of foreign judges.

Nearly 1,000 pages of text, unveiled last month after a deal was signed in December, would finally anchor Switzerland more firmly to the world’s largest single market.

But even the six market access agreements, which try to bring order to the tangle of previous arrangements, would still be on top of about 120 additional sectoral agreements that remain in place.

If approved, the new framework binds Switzerland to mirror changes to EU legislation in areas including the regulation of goods, migration, electricity and transport — or face retaliatory measures. Bern would have little influence over how the rules develop, but it would be obliged to pay €375mn annually into the EU budget.

© Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

Switzerland could be readmitted as an associate member into the bloc’s Horizon Europe science programme and become part of the nuclear science body Euratom and the student exchange scheme Erasmus.

The pact in many ways parallels the UK’s struggle of balancing sovereignty with EU market access. In May, the EU and UK agreed a number of changes from fisheries to energy as part of a relationship “reset”.

“There has been a pick-up in engagement and interest by the British in the negotiations we have been having with Brussels,” said one Swiss official.

The negotiations also come as both London and Bern are seeking deeper defence and security ties with the bloc after President Donald Trump’s threats to withdraw US guarantees that have underpinned Europe’s security since the second world war.

“The EU’s public position has long been that the Swiss and UK negotiations are separate, but in practice EU negotiators were keen to avoid setting precedents in one negotiation that might affect the other,” said Anton Spisak, an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

He added it was “no surprise” the same EU officials were involved in the Swiss negotiations and the recent UK-EU reset. There were nearly identical outcomes on issues like food safety (SPS) and governance in both agreements.

Now Switzerland will have to accept or reject the deal, a process that will take several years.

First will be a public consultation process until the autumn, then the text — possibly with some amendments — will be handed to parliament to start debating next year. The government aims to hold the referendum by June 2027, otherwise national elections later that year will push it into 2028.

The “dynamic alignment” — automatic adoption of changes to EU laws — are on six key areas: mutual recognition of goods standards, electricity, food safety, air and land transport and freedom of movement. Bern can lobby Brussels and EU members when they work on updates to those rules, but has no say in the final outcome and faces sanctions if it fails to implement the changes.

This will be uncomfortable for many Swiss given their deeply entrenched system of direct democracy.

“The Swiss have always followed these updates anyway. But they want to have the ability to choose. That is the key difference for us,” said one Zurich-based financier.

The agreements include an arbitration clause that ensures disputes are resolved by an independent panel — rather than unilaterally by EU courts — to address Swiss concerns over sovereignty and legal autonomy.

But when the case involves EU law, the arbitration panel must ask the European Court of Justice, the bloc’s top court, for a binding interpretation.

© Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

Carl Baudenbacher, a lawyer and expert on international business law, argued the ECJ would be the true legal authority behind the scenes.

“The arbitrators are legally obliged to ask the CJEU in the most important cases and the judgment is legally binding on the arbitration panel. It is essentially camouflage,” he said.

Like in the UK, ECJ jurisdiction and the “dynamic” adoption of EU laws are becoming lightning rods for Switzerland’s own Eurosceptic movement.

“The dynamic takeover of EU law and ECJ rulings ultimately changes the system of direct democracy in Switzerland. It downgrades our competitiveness,” said Kompass/Europa chief executive Philip Erzinger. The anti-EU group, started by private equity billionaires and other entrepreneurs, is gathering signatures to launch an initiative for the public vote on the matter.

“For example, you don’t need an agreement on free movement of people to hire people from foreign countries,” Erzinger added.

Switzerland’s far-right SVP is against the deal though it had found support on the left. The centrist parties such as the Liberals are yet to take a stance.

There is also a question of punishment if Switzerland votes no. In 2021, when Switzerland walked away from talks, the EU retaliated by downgrading Swiss participation in the Horizon Europe. That could happen again if the deal was not ratified by the end of 2028.

EU trade commissioner Maroš Šefčovič has refused to be drawn on possible action. But EU officials told the Financial Times that maintaining the status quo was not an option.

Swiss officials say the erosion of the existing bilateral agreements could have serious long-term ramifications, for example in terms of Swiss export capacity, security and transport between Switzerland and EU countries.

“If there is a No [vote], the EU feels this needs to be the end of the road for the bilateral way and the special treatment for Switzerland,” said an official familiar with thinking in Brussels.

Others, however, think it is high time to do a deal with Switzerland’s largest trading partner.

“We have been living with this drama since the 90s. Europe is our biggest trading partner and we need to solve the problem institutionally as opposed to sector by sector,” said Jean Keller, head of Geneva-based fund manager Quaero Capital.

“Yes, we need to make sure things like workers’ rights are protected, but finally finding a framework that is durable for us to do business in Europe is imperative.”

2

« en: Junio 30, 2025, 22:38:01 pm »

https://www.ft.com/content/59c07f63-3331-462b-b9e3-d1bcaea69fceUS dollar suffers worst start to year since 1973

Donald Trump’s trade policies and rising debt levels have sparked decline of more than 10% in first half of 2025

The US dollar is headed for its worst first half of the year since 1973, as Donald Trump’s trade and economic policies prompt global investors to rethink their exposure to the world’s dominant currency.

The dollar index, which measures the currency’s strength against a basket of six others including the pound, euro and yen, has slumped more than 10 per cent so far in 2025, the worst start to the year since the end of the gold-backed Bretton Woods system.

“The dollar has become the whipping boy of Trump 2.0’s erratic policies,” said Francesco Pesole, an FX strategist at ING.

The president’s stop-start tariff war, the US’s vast borrowing needs and worries about the independence of the Federal Reserve had undermined the appeal of the dollar as a safe haven for investors, he added.

The currency was down 0.2 per cent on Monday as the US Senate prepared to begin voting on amendments to Trump’s “big, beautiful” tax bill.

The landmark legislation is expected to add $3.2tn to the US debt pile over the coming decade and has fuelled concerns over the sustainability of Washington’s borrowings, sparking an exodus from the US Treasury market.

The dollar’s sharp decline puts it on course for its worst first half of the year since a 15 per cent loss in 1973 and the weakest showing over any six-month period since 2009.

The currency’s slide has confounded widespread predictions at the start of the year that Trump’s trade war would do greater damage to economies outside the US while fuelling American inflation, strengthening the currency against its rivals.

Instead, the euro, which several Wall Street banks were predicting would fall to parity with the dollar this year, has risen 13 per cent to above $1.17 as investors have focused on growth risks in the world’s biggest economy — while demand has risen for safe assets elsewhere, such as German bonds.

“You had a shock in terms of liberation day, in terms of the US policy framework,” said Andrew Balls, chief investment officer for global fixed income at bond group Pimco, referring to Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs” announcement in April.

There was no significant threat to the dollar’s status as the world’s de facto reserve currency, Balls argued. But that “doesn’t mean that you can’t have a significant weakening in the US dollar”, he added, highlighting a shift among global investors to hedge more of their dollar exposure, activity which itself drives the greenback lower.

Also pushing the dollar lower this year have been rising expectations that the Fed will cut rates more aggressively to support the US economy — urged on by Trump — with at least five quarter-point cuts expected by the end of next year, according to levels implied by futures contracts.

Bets on lower rates have helped US stocks to shake off trade war concerns and conflict in the Middle East to reach record highs. But the weaker dollar means the S&P 500 continues to lag far behind rivals in Europe when the returns are measured in the same currency.

Big investors from pension funds to central bank reserve managers have stated their desire to reduce their exposure to the dollar and US assets, and questioned whether the currency is still providing a haven from market swings.

“Foreign investors are requiring greater FX hedging for dollar-denominated assets, and that has been another factor preventing the dollar from following the US equity rebound,” said ING’s Pesole.

Gold has also hit record highs this year on continued buying by central banks and other investors worried about devaluation of their dollar assets.

The dollar slump has taken it to its weakest level against rival currencies in more than three years. Given the speed of the decline, and the popularity of bearish dollar bets, some analysts expect the currency to stabilise.

“A weaker dollar has become a crowded trade and I suspect the pace of decline will slow.” said Guy Miller, chief market strategist at insurance group Zurich.

3

« en: Junio 29, 2025, 23:11:26 pm »

https://www.ft.com/content/87683676-7de6-4642-bcea-bdf1a62ea34aGet ready to embark on a new era of financial repression

Tariffs are not the only flashpoint; another economic policy war is shaping up

© Liv Friis Larsen/Dreamstime

The trade war unleashed by Donald Trump may be just the precursor for much larger turmoil in the global economy. Whatever tariffs look like when the dust settles, deficits, surpluses and trade patterns will still be shaped by financial flows. It is only a matter of time before another economic policy war flares up — indeed it has already begun. Welcome to the new age of financial repression.

Financial repression refers to policies designed to steer capital to fund government priorities, rather than where it would flow in unregulated markets. In the postwar decades, western countries used regulation, tax design and prohibitions to both limit capital flows across borders and direct domestic flows into favoured uses, such as government bonds or housebuilding.

The US then spearheaded the decades of financial deregulation and globalisation that led up to (and led to) the global financial crisis. The US has now made abundantly clear that it rejects its traditional role in dismantling financial walls between countries and anchoring the global financial order.

Rumours of a “Mar-a-Lago accord”, which would manage the dollar’s value down while forcing global investors to discount and lock in lending to Washington, has produced shocked disbelief by other countries. But it is not just Mar-a-Lago: several policy proposals have surfaced recently that can fairly be grouped together as measures of financial nationalism.

These include a tax on remittances, levies on foreign investment stakes by nations with policies Washington disapproves of, and the promotion of dollar-denominated stablecoins and looser bank leverage regulations. The last two would both incentivise flows into US government debt securities.

While the US represents the biggest swing of the pendulum, other big economies have the same orientation away from letting finance flow freely.

China never stopped practising financial repression at scale. It has retained a non-convertible currency and manages its exchange rate. It uses a network of state-controlled or state-influenced banks, corporations and subnational governments to steer the flow of credit to outlets indicated by various economic development doctrines favoured by Beijing over the years. The latter has had both successes (the electric vehicle industry) and failures (the housebuilding bubble). China is also working on an alternative to the dollar-based international payment system.

Europeans have long been purist about free capital mobility — originally inside the EU’s single market, but also with the rest of the world. Yet there, too, attitudes are changing.

The influential reports of former Italian prime ministers Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi have emphasised that the bloc sends several hundred billion euros abroad every year when there are huge domestic funding gaps. This invites policymakers to adopt measures to redirect financial flows.

So does the agenda to unify national financial markets.

The aim of making the euro a more attractive reserve and investment currency has also been invigorated by Trump’s seeming disdain of the dollar’s role. A big EU-level borrowing programme suddenly looks at least conceivable, and an official digital euro is on the way. In parallel, the UK is trying to coax pension funds to put more savings in the hands of British businesses.

Europe may not end up with fully fledged financial repression, but it’s now open season for policies to steer financial flows where governments, not just markets, think they are most needed. In reality, commitments to climate and digital transitions and defence-related infrastructure leave no other choice.

What should we make of this return of financial state activism?

First, note that it comes with financial globalisation already in decline. Rapid growth in cross-border financial claims by banks halted in 2008. From nearly 50 per cent of the world economy at the start of 2008 such claims have shrunk to 30 per cent. That may have been partly offset by non-bank activity but in any case it happened without deliberate policies to keep money at home.

Second, complaints about other countries’ surpluses could quickly change if we end up in a scramble for the world’s available capital that will make the trade wars look like child’s play.

Third, much can go wrong. It is not that liberalised finance has covered itself in glory (it hasn’t). But state-directed finance is a high-risk activity, prone to cronyism and misallocation without safeguards. Still, it may be necessary. If everyone is going to try to keep more capital at home, it’s even more important to put it to the best uses.

4

« en: Junio 29, 2025, 22:53:53 pm »

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/26/business/crypto-industry-housing-market.htmlCrypto Industry Moves Into the U.S. Housing Market

Americans are finding ways to use digital currencies to help them buy homes, and new companies are forming to help people tap their home’s value to buy Bitcoin.

Rune Fisker

The nation’s largest mortgage finance firms will begin accepting crypto as an asset on a mortgage application, another significant step by the Trump administration to bring digital currencies into mainstream finance.

This week, President Trump’s housing director, William Pulte, said he would direct Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — the nation’s big mortgage finance firms — to consider home buyers’ crypto investments as part of their overall wealth in assessing whether they can afford a mortgage. Traditionally, a home buyer’s cash savings and stock investments are what mortgage lenders consider.

Fannie and Freddie, which are a critical cog in the housing market, buy mortgages from banks and establish a set of criteria for which borrowers’ mortgages they will accept.

The announcement by Mr. Pulte, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, on Wednesday comes as an increasing number of Americans have been using digital currencies to buy houses and new companies have formed to help them take advantage of their crypto holdings to buy real estate.

The crypto market and its many supporters have been pushing regulators in this direction for several years, raising concerns among consumer advocates that this lightly regulated and highly volatile investment asset is being tied to something as vital to the economy as the housing market.

And Mr. Trump has gone from a crypto critic to a big booster.

“In a world where regulatory enforcement has been largely taken off the table, the boundaries are getting pushed very quickly,” said Tyler Gellasch, a former lawyer at the Securities and Exchange Commission, who runs the Healthy Markets Association, a financial industry trade group.

But from home buyers and crypto enthusiasts, there is growing demand. In a recent survey, roughly 14 percent of home buyers said they planned to sell crypto assets to help get the cash to cover a down payment on a home, up from 5 percent in 2019, according to Redfin, the residential real estate brokerage company.

In 2017, David Doss sold some of his crypto holdings to raise cash for the down payment on a home in New Jersey. He said he would have preferred that there had been a way to keep his crypto while getting the cash equivalent but that option didn’t exist when he bought his house.

“The intersection of crypto and real estate is evolving pretty darn quickly,” [/color]said Mr. Doss, who advises wealthy investors on crypto investing. “It’s a meeting of the oldest asset class with one of the newest.”

Mr. Pulte’s order might have allowed Mr. Doss to keep some of his crypto holdings. It says that home buyers no longer have to sell their crypto for cash as part of the process of qualifying for a mortgage.

Crypto is gaining traction in the housing market as home sales have stagnated, leaving many unable to sell or buy a home or tap into their home’s equity through loans.

Several start-ups are already pitching crypto as a way to cut through the market’s current morass and jump start home sales.

One firm, Milo, founded by Josip Rupena, a former financial adviser at Morgan Stanley, offers investors a way to use Bitcoin as collateral for getting a home mortgage.

For a $1 million home, an investor posts $1 million worth of Bitcoin, which Milo puts into a secure account. The firm provides $1 million in cash to buy the home.

Milo then writes an equivalent mortgage that the home buyer is ultimately responsible to pay off. The interest tends to be a few percentage points higher than a normal mortgage, but the customer gets the benefit of not having to sell any crypto or pay capital gains. When the mortgage is paid off, Milo returns the Bitcoin to the investor.

Mr. Rupena said he had already underwritten $65 million of such mortgages, and he welcomed the F.H.F.A.’s policy shift on crypto.

Unlike most bank mortgages — like the ones Fannie and Freddie buy — Mr. Rupena’s firm does not require a homeowner to make a down payment. His firm finances 100 percent of the transaction, which most banks will not do and that is not likely to change with the new F.H.F.A. rule on crypto.

“This is the first step in getting crypto parity with other assets,” Mr. Rupena said of the F.H.F.A. decision.

Other firms are helping homeowners’ tap their home’s equity to buy crypto. The strategy is similar to so-called home equity investment contracts, which provide lump-sum cash payments to a homeowner in return for the right to share in the appreciation in a home’s value.

But instead of the homeowner using cash from the deal to pay for home improvements or a child’s college tuition, they are using it to buy only one thing: Bitcoin.

“Turn your home into a Bitcoin acquisition engine,’’ one of the start-up firms called Horizon, said in a post on X.

Here is how it typically works: Some of the firms loan the homeowner cash to buy Bitcoin based on the value of the equity in their homes. The firms typically make money by sharing in the appreciation in the value of a house when an owner sells it.

The deals are attractive because the homeowner does not need to make monthly payments during the life of the agreement, as they would with a traditional home equity loan.

As protection, some of the firms also place a lien on a house during the length of the contract — some of which can last for a decade.

Horizon debuted its offering at the Bitcoin conference last month in Las Vegas, where two of Mr. Trump’s sons were headline speakers.

Consumer advocates see reason for concern.

“My general impression is that taking any lien on your house to buy crypto is a terrible idea,” said Andrew Pizor, a senior attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, who specializes in mortgage financing. “This is the roof over your head, and you have to be cautious.”

All of these programs are in their infancy, so it’s too soon to say how much traction they will ultimately get.

Representatives for the companies said concerns about consumers being taking advantage of were overstated. Most prospective customers are wealthy investors. The firms also said they intended to be compliant with existing federal and state laws.

Harry W. Prahl, 35, who has been investing in Bitcoin since 2016, said he was interested in tapping the equity in both his home and in several apartment buildings he owned to buy more of the crypto currency.

Mr. Prahl has been talking to a company called Sovana, which was founded by a former Google executive, about using some of his real estate holdings as collateral to buy more Bitcoin. Sovana would buy Bitcoin, using a formula based on the equity in a person’s properties, and then put the crypto currency into a secure account. At the end of the deal, the person and the company would share the profits.

If Bitcoin drops in value, the property owner must make up the deficiency.

“It’s an alternative way to tap into that commercial equity that doesn’t effect the business,” Mr. Prahl said. “And not having to make any payment is a real killer feature.”

Though the details of the F.H.F.A.’s policy shift are scare, on its face it signals a shift in how the Trump administration is overseeing Fannie and Freddie. Under past administrations, the two firms have tended to be risk averse after nearly collapsing during the financial crisis when millions of homeowners defaulted on their mortgages.

In a post on X about the new policy, Mr. Pulte said he made the decision for Fannie and Freddie to count crypto among home buyers’ assets after “significant studying.”

He added that it was in “keeping with President Trump’s vision to make the United States the crypto capital of the world.”

5

« en: Junio 28, 2025, 10:07:52 am »

Esta simplificación ya es inquietante...realmente Trump está dispuesto a reventar el (su) sistema desde dentro y desde fuera? https://www.baha.com/Trump-Id-love-Feds-Powell-to-resign/news/details/64367399Trump: I'd love Fed's Powell to resign

United States President Donald Trump stated on Friday that he would "love" Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to resign, claiming that he is doing a "lousy job."

Speaking at a press conference at the White House, he insisted that Powell "with a stroke of a pen, could lower interest rates and save us hundreds of billions of dollars a year."

Finally, Trump stressed that his administration did "a great job" on inflation and employment, claiming that these are sufficient arguments for cutting interest rates.

6

« en: Junio 27, 2025, 23:19:59 pm »

7

« en: Junio 27, 2025, 22:48:36 pm »

https://www.ft.com/content/6cc4143c-c52c-4f0a-94d5-35a7180cb98aVon der Leyen proposes setting up EU-led alternative to WTO

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, right, yesterday proposed ‘redesigning’ the World Trade Organization © Yves Herman/Reuters

(...)As Donald Trump takes a wrecking ball to the international trade system, the EU is proposing to set up its own dispute settlement body in order to salvage free commerce, write Laura Dubois and Andy Bounds.

Context: EU leaders met in Brussels yesterday to discuss how to respond to US President Donald Trump’s tariffs, with a looming deadline on July 9. But they also touched upon other measures to preserve the international trade system.

European Commission president von der Leyen proposed that Brussels team up with the 11 other global economies of the CPTPP to form an institution to replace the WTO, which is struggling to contain global tensions.

“Asian countries want to have a structured co-operation with the EU, and the EU want the same,” von der Leyen said. “We can think about this as a beginning of a redesigning the WTO . . . to show to the world that free trade with a large number of countries is possible on a rules-based foundation.”

Von der Leyen declined to answer when asked if the US would be invited to join.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz welcomed the proposal, and said he had broached a similar idea with French President Emmanuel Macron and UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer.

“The WTO does not work anymore”, said Merz. “Can’t we gradually establish something with our trading partners around the world that institutionally replaces what we actually already envisioned with the WTO, namely a dispute settlement mechanism through an institution like the one the WTO was supposed to be?”

The US has been blocking the WTO’s binding dispute resolution system, although 29 members, including the EU and China, have created a voluntary alternative.

During the meeting, the commission also presented an outline of a potential trade agreement sent by the US. Most EU countries are in favour of Brussels negotiating a quick deal, but there are divisions over what to do if the US insists on 10 per cent blanket tariffs.

“We are preparing for the possibility that no satisfactory agreement is within reach,” von der Leyen said. “All options remain on the table.”

EU leaders also agreed to roll over the bloc’s sanctions on Russia in July, but its newest sanctions package still hangs in the balance. Slovakia will block the package unless it receives concessions from Brussels in its salvo against the last vestiges of Russian gas, Prime Minister Robert Fico said.

8

« en: Junio 27, 2025, 22:36:02 pm »

https://www.ft.com/content/d958aeaf-0bde-4168-a22b-83cdda867c12Nord Stream AG

Germany moves to block any attempts to restart Nord Stream

Berlin considers strengthening investment screening powers to stop any future investors reactivating gas pipelines

The Nord Stream project was launched by former chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who has close relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin. © IMAGO/Bihlmayerfotografie via Reuters Connect

Friedrich Merz’s government is examining ways to block any attempts to reactivate the Nord Stream gas pipelines linking Germany with Russia.

Berlin is considering strengthening its investment screening laws to ensure they catch any changes in ownership that could enable the pipelines to be reactivated, according to correspondence from the economy ministry.

In a written response to questions from Green MPs about the pipelines seen by the Financial Times, the ministry said it was “currently discussing whether there will be a legal amendment to investment screening”.

The pipelines, which are disabled after explosions damaged three of them in 2022, became a symbol of Berlin’s over-reliance on Moscow for energy. Germany, which in the past relied on Russia for more than 50 per cent of its gas supplies, has almost entirely weaned itself off Russian fossil fuels as Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine grinds on into its fourth year.

The German government was alarmed by reports in the Financial Times in March that Kremlin-linked Russian and US businesspeople were seeking to reactivate the pipelines, prompting Merz to start discussions with officials in Berlin and Brussels about keeping them closed.

Berlin has no state control over any of the four Nord Stream pipelines and under current legislation could do little to prevent any changes in ownership in the Swiss-based entity that owns them, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

It would be required to grant a technical certification if the pipelines were to be reactivated, but ultimately lacks the power to stop that unless the rules are changed, the people said.

The German chancellor has pushed for a ban on the pipelines as part of the EU’s upcoming round of sanctions against Russia for its war in Ukraine.

However, EU leaders failed this week to approve the new package of sanctions, because of Slovakia’s opposition.

US investor Stephen Lynch, one of those seeking to put the pipelines back in use, was invited to a meeting at the German economy ministry to discuss his plans on May 6, according to a person with direct knowledge of the talks. The meeting was first reported by Die Zeit.

Asked by Green MPs about the Lynch meeting, the economy ministry said no meeting took place at senior levels, but that officials often exchange information with institutions and individuals in relation to their areas of expertise.

US investor Stephen Lynch believes that Europe will one day be ready to buy Russian gas again, according to a person familiar with his thinking. © Michael Brochstein/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect

Lynch believes that Europe will one day be ready to buy Russian gas again, according to a person familiar with his thinking. The US investor does not believe it would be necessary to undertake the costly work of repairing the damaged pipelines, arguing that one would be enough to meet European demand.

Lynch did not immediately respond to a request for comment from the FT.

Under German law, Berlin can block ownership changes related to non-EU investors in critical infrastructure if the transaction is deemed “a threat to Germany’s public order or security”.

Since the company operating the Nord Stream pipelines is based in Switzerland, which is part of the European Free Trade Association, a takeover would not be subject to an investment review under current rules, it said.

The Nord Stream project was launched by former chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who has close relations with Russian President Putin.

Even before Moscow started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the pipelines were a source of contention between Berlin and Washington, with the first Trump administration pressuring then chancellor Angela Merkel to cut her country’s reliance on Russia.

A spokesperson for Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov said on Thursday that efforts to block the pipelines resuming showed Europe’s “exasperation” at Russia’s independent policy, which he said Russia would pursue “whatever the cost.”

The recent activation plans have reignited a debate in Germany about cheap Russian gas.

Far-right Alternative for Germany wants to bring the pipelines back online, while some prominent CDU and SPD politicians have also backed such calls to alleviate higher energy prices and help Germany’s struggling industry.

However the German government told the Green MPs that it supported the EU commission’s efforts to “gradually end energy imports from Russia into the EU”.

“This will make an important contribution to increasing the EU’s energy independence and security,” it wrote. “Germany already no longer purchases Russian pipeline gas. No Russian LNG is delivered to German LNG terminals either.”

9

« en: Junio 25, 2025, 22:23:53 pm »

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/new-home-sales-plunge-to-a-7-month-low-as-buyers-struggle-with-high-prices-expect-more-weakness-in-the-months-ahead-25bee456New-home sales plunge to a 7-month low as buyers struggle with high prices. Expect more weakness in the months ahead.

The drop in new-home sales was steeper than expected

Home builders saw weak demand from buyers in the spring home-selling season. Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Sales of new homes plunged in May as buyers continued to stay away from the market, even as builders threw discounts and deals at them.

Sales of newly built homes could remain depressed as buyers continue to deal with the same affordability conditions as they have seen in the last few years. Home prices remain high and mortgage rates are still at 7%, making homeownership a tough proposition for many.

New-home sales in the U.S. plunged by 13.7% in May, to the lowest level since October 2024. Sales fell the most in the South, followed by the Midwest.

The overall drop in new-home sales was larger than economists surveyed by Dow Jones Newswires and the Wall Street Journal had expected.

The median sales price of a newly built home was up 3.7% to $426,600 in May.

Economists said to expect further weakness ahead.

“The May pace of home sales, combining new and existing sales, was the softest to date in 2025. And I expect further weakness to come,” Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Santander U.S., wrote in a note. “Mortgage rates have risen, and households are less upbeat about the economic outlook, both of which are likely to eat into housing demand.”

In a note, analysts at Raymond James wrote: “We should expect home prices to show some weakness going forward, as we expect the housing market to weaken during the rest of the year under the pressure of still-high mortgage interest rates.”

Builders have begun to pull back on new construction because of the depressed demand. In May, housing starts, a measure of the pace of new construction, fell to a five-year low as builders felt less confident about their ability to sell those homes.

They’re also throwing incentives at buyers and slashing prices to move inventory. In June, 37% of builders said they have cut home prices, with an average price reduction of 5%.

The incentives have paid off for some builders. In its second-quarter earnings report, Lennar reported that its price-cut and incentive strategy helped boost sales.

But the months ahead could be even more challenging for builders, with potential impact from the Trump administration’s tariffs and immigration raids. Immigrant labor is a big part of the construction industry’s workforce, and the push to deport undocumented workers could affect builders’ ability to deliver new homes, as Construction Dive reported recently. The National Association of Home Builders, meanwhile, previously estimated that tariffs could add an additional $10,900 to the cost of a home.

“Somebody who’s building has to factor those costs in, and on a long-term basis has to raise their costs,” Jeff Lichtenstein, founder of Echo Fine Properties, a real-estate company in Florida, told MarketWatch. “Right now, builders are giving away all sorts of deals on things” to move already built homes.

In May, there were about 507,000 new homes for sale, which was the highest level since 2007, Stanley said.

But moving forward, new homes may be more expensive due to tariffs and high construction costs, Lichtenstein noted.

10

« en: Junio 25, 2025, 18:52:02 pm »

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-06-25/us-new-home-sales-drop-to-seven-month-low-on-poor-affordabilityUS New-Home Sales Drop by Most Since 2022 on Poor Affordability

Newly built homes in Loudonville, New York.Photographer: Angus Mordant/Bloomberg

US purchases of new homes fell in May by the most in almost three years as rampant sales incentives fell short of alleviating affordability constraints.

Sales of new single-family homes decreased 13.7% to a 623,000 annualized rate last month, a seven-month low, according to government data released Wednesday. That was below all estimates in a Bloomberg survey.

The latest results show homebuilders are sitting on rising inventories amid mounting economic challenges, including mortgage rates stuck near 7%, higher materials costs due to tariffs and a slowing labor market. While builders are offering subsidies to reduce customers’ financing costs, the concessions are yielding diminishing returns and encouraging many builders to slow construction.

“This spring and summer are shaping up to be very tough for the real estate market,” said Heather Long, chief economist for Navy Federal Credit Union. “Buyers are staying on the sidelines as they worry about uncertainty and high mortgage rates.”

The home sales report showed a slight increase in the number of new houses for sale in May, to the highest level since 2007. That represented 9.8 months of supply at the current sales rate. The number of completed homes for sale rose to 119,000, an almost 16-year high.

The median sales price increased 3% from a year ago to $426,600 last month, marking the first year-over-year price gain in 2025. More limited inventory in the resale market has allowed prices to steadily rise there on an annual basis since mid-2023.

Sales last month in the South, the biggest US homebuilding region, slumped 21%, the most in nearly 12 years. Contract signings in the West and Midwest also fell, while they rose in the Northeast.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“We had forecast a slowdown in sales volumes, but the decline in activity — especially in the South — exceeded our expectations. With inventories rising and affordability still a problem for the median prospective home-buying family, we expect prices to face headwinds throughout the year.”

— Stuart Paul, economist

With increasingly bloated inventories and sagging sales, ground-breaking on single-family homes last month remained sluggish, according to figures out last week. Economists forecast residential investment will remain a soft spot for the economy in coming quarters.

Confidence among homebuilders stands at the lowest level since December 2022, while at the same time an increasing supply of previously owned homes emerges as an additional threat to builders, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Drew Reading said in a recent note.

Builder Lennar Corp. has indicated a willingness to lower home prices and accept smaller margins by maintaining its volume of construction in order to preserve market share.

New-home sales are seen as a more timely measurement than purchases of existing homes, which are calculated when contracts close. However, the data are volatile. The government report showed 90% confidence that the change in new-home sales ranged from a 26.8% decline to a 0.6% decline.

11

« en: Junio 25, 2025, 17:13:18 pm »

https://www.baha.com/Trump-Ending-Ukraine-crisis-harder-than-it-seems/news/details/64350499Trump: Ending Ukraine crisis harder than it seems

United States President Donald Trump insisted on Wednesday that his earlier comment that he would end the conflict in Ukraine "in 24 hours" when he returns to the White House was sarcastic, as solving it is "more difficult than anyone would imagine."

Speaking to the press during the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) summit in The Hague, Trump said that Russia has been hard to negotiate with, while also criticizing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for making "some problems" too.

Still, he described the meeting he had with Zelensky on the sidelines of the summit as good.Furthermore, Trump noted that the US will take a look at whether it can make the Patriot missiles available to Ukraine.

12

« en: Junio 25, 2025, 09:00:51 am »

https://www.baha.com/trump-seemingly-shares-ruttes-private-message/news/details/64342315Trump seemingly shares Rutte's private message

United States President Donald Trump posted on Tuesday a screenshot of what he claimed was private message North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Secretary-General Mark Rutte sent him.

In the message, Rutte allegedly congratulated Trump on his "decisive action in Iran, that was truly extraordinary, and something no one else dared to do. It makes us all safer." "Donald, you have driven us to a really, really important moment for America and Europe, and the world. You will achieve something NO American president in decades could get done," Rutte supposedly wrote. "Europe is going to pay in a BIG way, as they should, and it will be your win."

Rutte reportedly texted Trump ahead of the NATO summit in The Hague, which will be held on June 24 and 25. https://www.baha.com/Rutte-totally-fine-with-Trump-sharing-his-message/news/details/64346491Rutte 'totally fine' with Trump sharing his message

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte stated on Wednesday that he is "totally fine" with United States President Donald Trump publicly sharing the message he sent him.

Speaking to reporters ahead of the NATO Summit in The Hague, Rutte said he "absolutely" did not find the move embarrassing as what is in the text messages is a "statement of fact." The NATO head said that he is "hopeful and cautiously optimistic" about allies reaching the 5% defense spending target, but that it would not be possible if Trump was not elected US president.

On Tuesday, Trump posted screenshots of a series of texts Rutte sent him ahead of the summit in which the NATO chief praised the US president for taking "decisive action in Iran" and for being on his way to do "something NO American president in decades could get done" by convincing NATO allies to boost defense spending to 5%.

13

« en: Junio 24, 2025, 21:38:22 pm »

El artículo es de febrero de este año. https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2025/02/how-much-is-the-u-s-housing-market-worth/How Much is the U.S. Housing Market Worth?

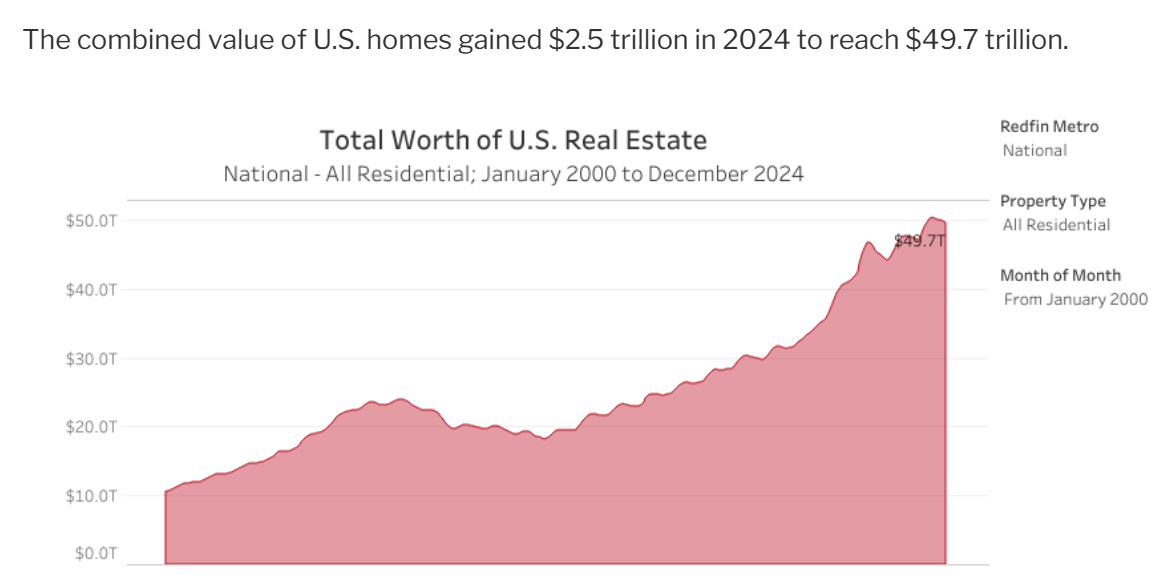

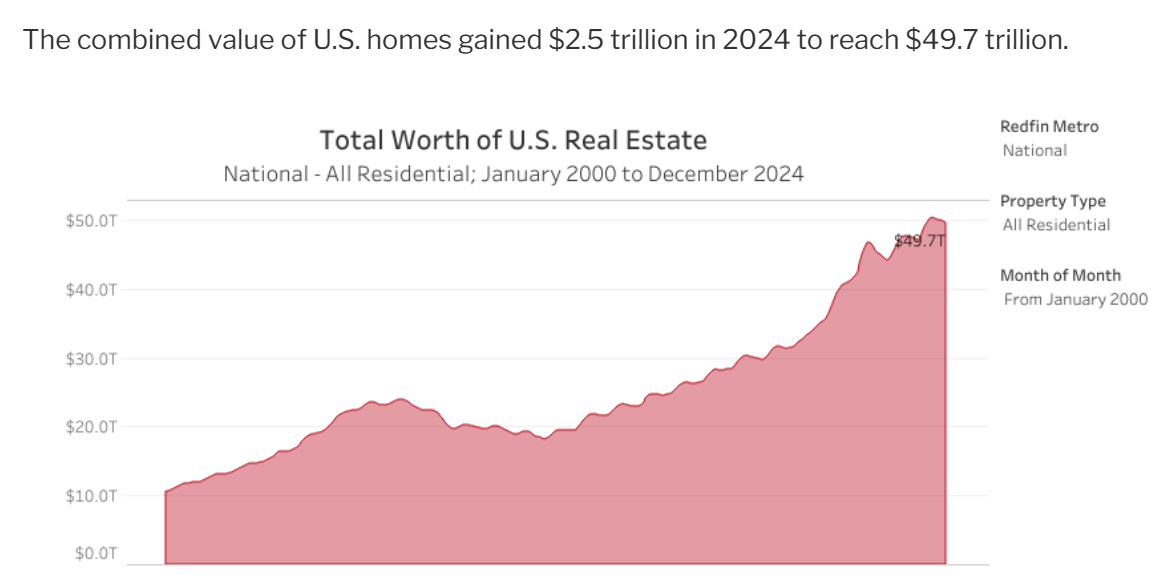

According to Redfin, the U.S. housing market is now worth a stone’s throw from $50 trillion:

Depending on the day, that puts the housing market roughly on par with the total value of the U.S. stock market. In the past decade alone the total value of the housing market has more than doubled (from $23 trillion in 2014).

Considering mortgage rates averaged nearly 7% in 2024, it’s hard to believe housing prices were up another 5% in 2024. That gain follows annual housing returns of +19%, +6%, +6% and +4% from 2021-2024.

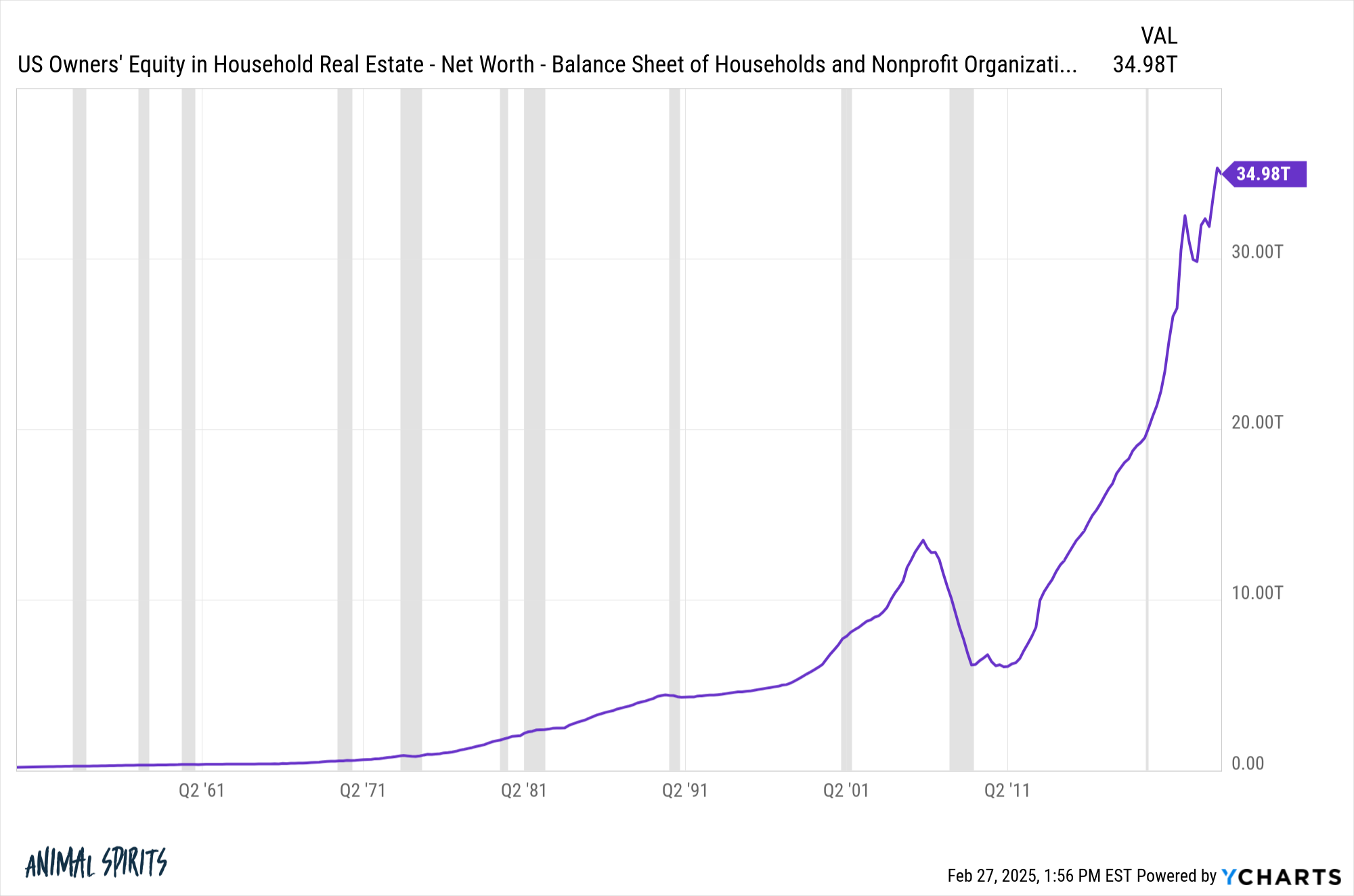

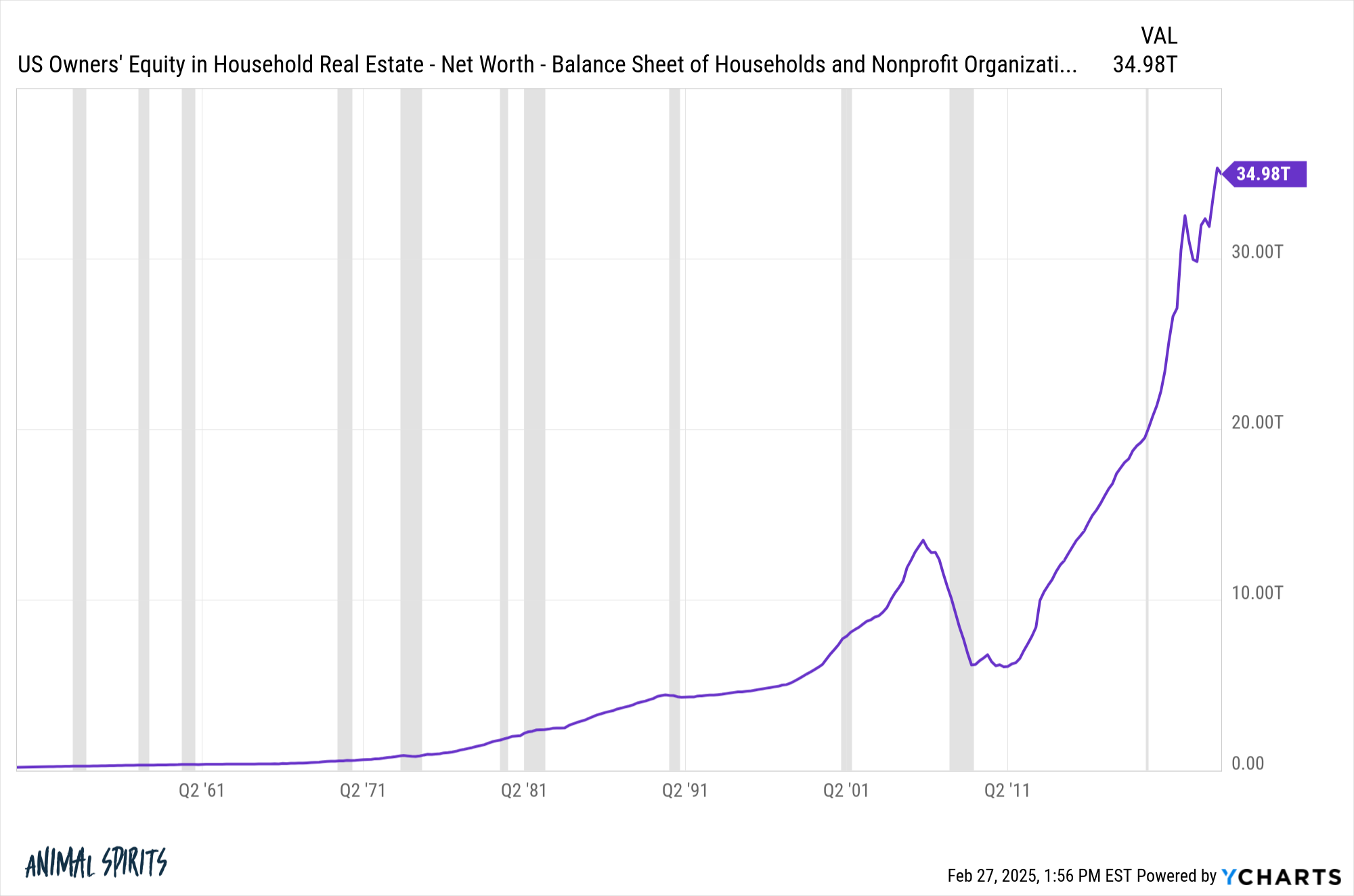

When you throw in the fact that 70% of that $50 trillion is equity, Americans are sitting on some healthy housing gains.

(...)

14

« en: Junio 24, 2025, 18:09:30 pm »

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/trump-lashes-israel-iran-bid-121434693.htmlTruce Between Israel and Iran Back On After Trump Lashes Out

(Bloomberg) -- Israel and Iran appeared to be honoring a ceasefire agreement unexpectedly announced by US President Donald Trump overnight, after the American leader reacted angrily to early breaches of the deal by both sides.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to hold off on further strikes after a conversation with Trump on Tuesday, according to a statement from his office. Israel had destroyed a radar complex near Tehran after the truce came into effect as of 7 a.m. local time, the PM’s office said, but this was in response to three missiles from Iran.

Reports of attacks in the early hours of the peace accord triggered a furious reaction from Trump, who had declared the war over late Monday after 12 days of fighting. “DO NOT DROP THOSE BOMBS,” read one post on his Truth Social platform, directed at Israel in particular. “IF YOU DO IT IS A MAJOR VIOLATION.”

The US leader’s frustration boiled over when he stopped to take questions from reporters before heading to a NATO summit in The Hague. “We basically have two countries that have been fighting so long and so hard that they don’t know what the fuck they’re doing,” he told them on the White House lawn, before marching toward the presidential helicopter.(...)

15

« en: Junio 24, 2025, 18:04:51 pm »

https://www.ft.com/content/2d50ae42-0dd4-448c-acde-fa2e8a4a5bd3Gulf expat bubble punctured by missiles

Overseas workers moved to an oasis of prosperity and security in the region. Then the explosions started

Many expats are worried about travel disruptions that could delay or derail summer holiday plans © Reuters

The safe streets of Qatar are a key draw for foreign workers, who enjoy tax-free incomes and the Gulf’s mild winter weather. But on Monday evening, a volley of Iranian missiles heading for a US military base burst that comfortable bubble.

The sound of explosions — shaking windows and activating emergency sirens — triggered panic inside Doha’s plush Villaggio Mall. Shrieks filled the cavernous hall and shoppers bolted for exits. Video footage showed a black shoe abandoned in the hurry. Across the usually tranquil city, parents comforted children frightened by the blasts.

Among millions of mobile expatriates who power the oil-rich region’s economies and make up about half the Gulf’s population, Iran’s attack on Qatar has prompted questions about safety in countries long regarded as oases of prosperity and security in a troubled region.

The region’s foreign workforce ranges from well-paid finance and energy executives to blue-collar workers mainly from South Asia, who build the countries’ infrastructure and keep them running.

Many foreign workers are phlegmatic. Some are battle-tested by previous attacks by Iran-aligned Yemeni Houthi rebels and other proxies on energy infrastructure in 2019 and 2022, which struck Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, or by the regional boycott of Qatar during Donald Trump’s first term.

But the Gulf’s population has swelled in recent years. For many newcomers, this is their first experience of a Middle East war — even if indirectly.

“The reaction depends on how long you’ve been in the region,” said a banker based in the UAE. “Some of the newer people, even in Dubai, were like ‘oh my god, this isn’t what I signed up for’.”

Since Israel attacked Iran less than two weeks ago, the Gulf monarchies have pushed for an end to hostilities and return to talks. They hoped to avoid wider regional escalation and avoid being caught in the crossfire as a result of the several US military installations in Gulf states.

Iran’s strikes on Monday targeting the US’s biggest military base in the region came in retaliation for US attacks on its nuclear infrastructure.

Later in the day, Trump announced that Iran and Israel had agreed to a ceasefire, though that appeared shaky on Tuesday morning after Israel said Tehran had launched fresh missiles, and threatened to respond.

The Iranian missiles that ripped through Qatar’s sky had mostly been intercepted by air defences, causing no casualties.

But if this was a display of military theatrics, “I prefer the safe £200-a-ticket, inaccessible to average people, London type of theatre”, quipped one expatriate Doha resident on Monday night.

The mood on Tuesday morning was “tense but relieved”, said a Palestinian-British-Canadian expatriate in Doha. During the attack he said his reaction was “WTF” but by the morning he felt secure, pleased at how the government had maintained services such as internet and electricity.

On social media, some residents called the night’s events insignificant compared with Israeli bombing that has flattened Gaza.

But one senior British expatriate based in Doha for two decades said his peers were “fairly shell-shocked”.

“Fortunately the US base is well out of town,” he added. “Still, not very pleasant to go through, and the future uncertainty is no doubt on everybody’s mind.”

Several organisations sent emails telling staff that Tuesday would be a normal working day, and the senior expatriate expected most employees to show up.

In Dubai, the region’s second-biggest city after Riyadh, some expatriates had already planned out overland escape routes to Oman. At one company, employees on a security call asked for plans to evacuate, but were rebuffed.

A view of Dubai Marina. Some professionals said they felt confident the Gulf would suffer little to no economic impact © Andrew Aitchison/In Pictures/Getty Images

WhatsApp groups buzzed with expats questioning the safety of staying in the region during the unpredictable Trump era, and some expatriates even dubbed Europe-bound flights through the Gulf as navigating “missile alley”.

But many foreigners were sanguine, with their main concern the disruption to aviation and its potential to delay or derail summer holiday plans.

Phil Miles, associate managing director for enterprise security risk management at adviser Kroll, said some clients had already “postponed non-essential travel to the region and are providing staff with increased flexibility to work from home”.

Some professionals said they felt confident the Gulf would suffer little to no economic impact.

“There was no disruption to energy flows, plus the ceasefire was announced so quickly — these are all positive,” said Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank. “We’re also in the quieter travel and tourism period for the region. So we’re not making any non-oil forecast changes.”

For one Dubai-based economist, “the Saudi economic slowdown matters more in the Gulf than all the drama of the last few days”.

But not all are convinced. Gaffour, a limousine driver in Doha, has seen business plummet since the World Cup in 2022, and fears further economic decline as a result of the growing geopolitical tensions.

“There still isn’t any business,” he said. “All my friends are worried.”

|